First published in Eurasia Review on 1 June 2021. An extended version has appeared in Global South Colloquy, 1 June 2021.

“One cannot but find the emerging situation in Lakshadweep Archipelago very bizarre, unheard in the life-world experiences of the inhabitants of the Island,” says Ali Manikfan, the winner of this year’s Padma Shri, one of India’s highest civilian awards. The 83-year-old ‘Man in Million’ from Minicoy Island (Lakshadweep) is an offbeat marine ecologist and a versatile genius. In his conversation with this writer, Manikfan endorsed the sentiments of thousands of Islanders who have been agitated over what they called ‘stringent regulations’ foisted upon them by the administration of the Union Territory of India (UTI). Manikfan makes no bones about his overt disappointment with the actions of the present dispensation in Lakshadweep—the smallest UTI off the southwest coast of the Indian state, Kerala. He poses a fundamental question—”why unsolicited regulations are forced upon the people so hastily by the new Administration in the Island without consultation and discussion.” Manikfan, who knows the Archipelago for decades closely, is sure that the new rules, if put in place as they were, “would spell disaster for the fragile ecosystem of the Island as well as for the sustainable livelihood of the inhabitants.”

Ali Manikfan

Even as the Save Lakshadweep campaign gets snowballed with new locales of agitation emerging in the Island as well as in Kerala—the state which has historical and cultural connectivity with Lakshadweep—there are also attempts which make quiet a dent in the social harmony and secular matrix of the Island society. While there are allegations of a Hindutva project behind the recent set of measures, the right-wing forces, in turn, accused the agitators of sheltering a Jihadi agenda in the Island. Such accusations and stereotypes are not quite unusual in Muslim dominant areas in India (Venkatesan 2021). The social media users of both camps are now all agog, dreadfully at the communal mobilisation.

However, Manikfan, like many others this writer contacted, has apprehensions about such narratives being blown out of proportion. Insofar as the real issues have entirely different dimensions, the narratives in circulation need to be seen with great caution, vigilance and wisdom, they all sounded off.

There are yet others who squelch by setting up the ‘big picture’ of India’s ‘security and maritime interests’ in the Indian Ocean—arguing that Lakshadweep comes under India’s new maritime security architecture (Chari 2021). The national security narrative, however, has little relevance for the ordinary people in the Island who know that this ‘externalising’ strategy cannot save the Island from the impending ecological threats which would get further push in the days of fast deteriorating climate change scenario.

‘Transforming’ Lakshadweep?

While the present UT Administrator Praful Khoda Patel has been in the eye of the storm, one must necessarily take on board developments prior to his assumption of office in December 2020. It was NITI Aayog (the successor of the dismantled Planning Commission of India) which ushered in a ‘master plan’ for massive tourism development initiatives in Lakshadweep and Andaman Nicobar Islands in its May 2019 document Transforming the Islands Through Creativity & Innovation. The document concluded saying that it “has produced a win-win situation for the Government, the islanders and the private sector, all expecting to get high dividends. Return is expected to be huge in terms of creation of jobs and generation of additional income for the islanders, profit for the private sector as well as revenue for the Government exchequer.” It suggested “expeditious implementation of the formulated strategies and the planned projects with participation of the islanders and the private sector will make the identified islands a role model of sustainable development, which can be replicated in other islands or even in other parts of the country” (NITI Aayog 2019). While making some customary references to ‘ecological security,’ ‘island eco-system’ etc the Island Authority resolved to undertake ‘holistic development package’ in Lakshadweep through Public-Private Partnership (the ‘PPP’) on Design, Build, Finance, Operate and Transfer (the ‘DBFOT’) basis.

In a meeting of the Island Development Agency (IDA) chaired by the Union Home Minister Amit Shah on 13 January 2020, it was noted that “Model tourism projects both Land-based and Water Villas were planned and bids have been invited for private sector participation. As a unique initiative, to spur investment, it was decided to obtain clearances for implementation of the planned projects up-front. All necessary clearances would be in place before bids finalization” (India, Ministry of Home Affairs 2020).

In line with this, the Lakshadweep Administration brought out The Lakshadweep Tourism Policy 2020 following the proposals of NITI Aayog and the decision of the IDA. One of the major statements of the policy runs like this: “The Administration will gradually withdraw from its present role as tourism service provider, but steadily perform as a facilitator and regulator.” The policy also highlighted other projects proposed to be undertaken by the Lakshadweep Administration in coordination with NITI Aayog for Public-Private Partnership based development of Island water villa resorts projects in the island of Kadmat, Minicoy and Suheli Cheriyakara (Union Territory of Lakshadweep 2020). Reports had indicated that the project would be implemented by Lakshadweep’s Society for Promotion of Nature Tourism and Sports (SPORTS) with an opening investment of Rs. 266 crore (and supplementary investments of up to Rs.788 crore were also expected from the private sector).

While the Islanders were caught unawares of the implications of the massive tourism projects, hundreds of scientists and experts from different universities and research institutions in India had warned the long-term and short-term ecological consequences of the ‘master plan’ (The Hindu, 14 March 2020). It was in the background of the efforts underway in the implementation of the proposed projects that Praful Patel took charge following the demise of Dineshwar Sharma, former chief of the Intelligence Bureau, who served as 34th Administrator of Lakshadweep, in December 2020. Patel was already serving as the Administrator of the Union Territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu. The five months since his assumption of office in Lakshadweep have been the most tumultuous period in the Archipelago’s history. The most controversial regulations being put in place by the new Administration are, The Lakshadweep Animal Preservation Regulation, 2021, The Prevention of Anti-Social Activities Regulation (PASA), The Lakshadweep Panchayat Regulation, 2021 and Lakshadweep Development Authority Regulation 2021. Experts working on fragile ecosystem management and governance argue that this new regime of regulations will set the ground for unimaginable collateral damage and widespread displacement in the Archipelago.

Evidently, Kerala has high stakes in Lakshadweep due to its historical, cultural and economic connections. There are other geopolitical and legal factors in the making of its relations with the Island, which included the ports facility as well as the judicial dispensation through the High Court of Kerala. Trade with Lakshadweep is also a very crucial for business communities in the coastal cities of Kerala. Moreover, hundreds of Lakshadweep students are studying in the colleges and universities of Kerala, including in professional educational institutions. It is quite natural, therefore, that voices of dissent and resistance are strident in the state irrespective of political or cultural differences.

It was in this background that on 31 May the Kerala Legislative Assembly (2021) unanimously passed a resolution declaring solidarity with the people of Lakshadweep and called for the intervention of the Union Government to restore normal life in the Island. Introducing the resolution, the Chief Minister said that the people of Lakshadweep were undergoing a difficult situation and “their culture and tradition are under threat” following unprecedented measures introduced by the administrator ignoring local protests. “Even their food habits and livelihood are under threat,” he said. Earlier, M.K. Stalin, the Chief Minister of another south Indian state Tamil Nadu, also expressed deep concerns over the developments in the Island and sought Administrator Patel’s recall.

Archipelago of Diversities

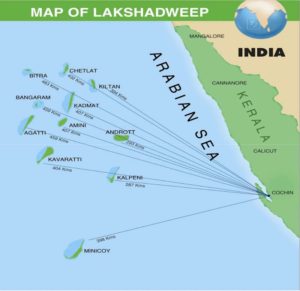

Lakshadweep—formerly known as Laccadive, Minicoy, and Amindivi Islands—is the smallest Union Territory of India, formed in 1956. It is an archipelago of 36 islands with an area of 32 sq km with a population of a little less than 70,000. There are only 11 islands inhabited by the people. It is a uni-district Union Territory and comprises of 12 atolls, three reefs, and five submerged banks. It was redesignated as Lakshadweep in 1973. Kochi, Kerala’s coastal city, is well connected with the main islands which are 220-440 km away in the Arabian Sea. The natural sceneries, serene beaches, lagoons and a rich repertory of flora and fauna make Lakshadweep one of the finest places in South Asia. Willian Logan’s 19th century volume—Malabar Manual—speaks about the islands’ “radiant beauty” as quite peculiar— “such as few spots on earth can produce” (Logan 1887/2000: 4). The two volumes of Malabar Manual have frequent references to its history, people, society and economy.

Nearly 94 per cent of the population in the Island are indigenous Muslims and they are mainly following the Shafi School of the Sunni Sect of Islam. They are descendants of the people migrated from the Malabar coast and speak Malayalam (except in Minicoy where Mahl is spoken which has Dhivehi written script as in Maldives). According to the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) (Union Territories) Order, 1951 (C.O.33), the whole indigenous community has been classified as ‘Scheduled Tribes’ because of their economic and social backwardness. As per the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes list (modification orders), 1956, the inhabitants of Lakshadweep who and both of whose parents were born in these islands are treated as Scheduled Tribes.

The social life-world of the Islanders is relatively peaceful with the lowest percentage of crimes and other offences recorded by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). And no crime against women was reported by the NCRB in the recent past (India, Ministry of Home Affairs 2019).

Fishing is the mainstay of the people, besides coconut cultivation. The sea around the Island is highly productive. There are no industries in Lakshadweep and the export potential is limited to marine products and coconut related produce. The Island has moderate facilities for health and higher education, and people depend on states like Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Telangana etc. The literacy rate is 93.55 per cent. Tourism is basically promoted through the nodal agency called the Society for Promotion of Nature Tourism and Sports (SPORTS), formed by the Lakshadweep Administration in 1982. Though it has not been making much headway due to several endogenic geographical constraints, it is this sector which has, of late, attracted considerable attention of several private players.

The cultural life-world of the islanders is also marked by a high degree of inter-communal and inter-personal rapport. It is this high level social and inter-cultural social capital that is being disfigured by communal forces in the mainland. According to M.N. Karassery, a noted social critic and writer, “many narratives emerging from the current row are distorted and exaggerated.” The presence of ‘Jihadi Islam’ and ‘the rule of Shariat’ is one such discourse. Karassery who has had long and intimate connections with the Island, which spans over decades, and had translated many ‘Arabi-Malayalam’ texts from Lakshadweep told this writer that the people are basically following matrilineal system which is alien to Shariat. According to Logan, people in the island used to follow monogamy and “the women appear in public freely with their heads uncovered, and in Minicoy take the lead in almost everything, except navigation” (Logan 1887/2000 Vol. II: ccIxxiv).

Lakshadweep is culturally diverse, and Karassery acknowledges that there are different castes (such as Koyas, Malmis and Melacheris) and atypical Islamic traditions in the island. The most dominant sect is Sunni Muslims with diverse cultural and ideological orientations. For example, a good number of Muslims have affinity with the Sunni faction of Kanthapuram A. P. Aboobacker Musliyar. They follow practices like Ziayarat (visit of tomb of Muslim saints), Ratheeb and Maulood. There are also some adherents of Nadvathul Mujahideen, Jamaat-e-Islami, Ahamadiyy, Quadiriyya and Rifai sects of Sufis. Followers of Mujahideen were called ‘Wahhabists’ and there were interesting encounters between them and other traditional sects in the past, as told by Ali Manikfan. Brian J. Didier, an Anthropologist in the Department of Anthropology at Dartmouth College, had studied such encounters within the traditions of Islam in the Island (Didier 2004). Notwithstanding differences among themselves on Islamic practices and rituals, Lakshadweep Muslims never resorted to any violent or other extreme form of religious protests or resistance. Curiously, the Tourism Policy 2020 also mentioned about the ‘Ziyarat Tourism’ as part of promoting ‘pilgrimage tourism’ with several tombs of Sufi saints in the islands.

Unjust Regime of Regulations

According to N.P. Sreejesh, a scholar in International Relations who taught at the Andrott Centre of the University of Calicut in Lakshadweep for nearly three years, the narratives of ‘beef ban’ and ‘underdevelopment’ tend “to deviate the real issues the people of the Island are now confronted with.” He says that it is a gross exaggeration to say that the people are against ‘development.’ They are actually posing a crucial question, if Lakshadweep “can replicate the Maldives model?” This is sensible considering the limits and potential of tourism in the Island.

The four regulations put in place by the Administration of Lakshadweep have generated widespread protests within and across the mainland.The Prevention of Anti-Social Activities Regulation (PASA), if implemented, can empower the administration to detain anyone without public disclosure for up to one year (Union Territory of Lakshadweep 2021a). This is at a time when crime cases in the Island are at the lowest. The Save Lakshadweep Forum has already exposed the arguments of the Lakshadweep Collector Asker Ali who said in a press conference in Kochi that the said regulation was drafted in the context of the recent “confiscation of 300 kg heroin and five AK 47 rifles by the Indian Coast Guard from a fishing boat that was passing through the sea, “along one of the Islands.” But the confiscated boat, according to the Indian Coast Guard (ICG), was reported to be from Sri Lanka and the fishermen on board were also Sri Lankan nationals and the ICG also made no claim of any ‘Lakshadweep connection’ in the incident (Press Information Bureau 2021).

Many believe that The Lakshadweep Animal Preservation Regulation, 2021 will end up with a ban on the slaughter of cows, calfs of a cow, bulls and bullocks with provisions for severe penalties in case of violation. For instance, Section 8 of the regulation says: “(1) No person shall directly or indirectly sell, keep, store, transport, offer or expose for sell or buy beef or beef products in any form. (2) Whenever any person transports or causes to be transported the beef or beef products, such vehicle or any conveyance used in transporting such beef or beef products along with such beef or beef products shall be liable to be seized by such authority or officer as the Administrator may appoint in this behalf.” Section 10 Clause (2) of the regulation says: “Whoever in contravention of the provisions of sub-section (1) of section 5, slaughters any animal as specified in sub-section (2) of section 5 shall, on conviction, be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to imprisonment for life but shall not be less than ten years and with fine which may extend to five lac rupees but shall not be less than one lac rupees” Union Territory of Lakshadweep 2021b). The Government claim is that more than 85 per cent of the Indian states and UTs have legislations on banning or restricting slaughter of animals, and Lakshadweep was the only remaining UT in India without such a legislation. Ironically, India remains the fourth largest exporter of beef in the world (1.2 million metric tons annually).

The Lakshadweep Development Authority Regulation 2021 will empower the government to take any piece of land owned by any citizen in the island for ‘development’ purposes. And ‘development’ is defined by the new regulation as the “carrying out of building, engineering, mining, quarrying or other operations in, on, over or under, land, the cutting of a hill or any portion there of or the making of any material change in any building or land, or in the use of any building or land, and includes sub-division of any land” (Union Territory of Lakshadweep 2021c). Experts say that this definition itself is an invitation to disaster considering the massive programmes envisaged under tourism development.

The new Lakshadweep Panchayat Regulation, 2021 is also fraught with dangerous implications. The UT Administration is set to take over many subjects which the Panchayat Raj institutions in the Island have been handling over decades. The regulation is, according to experts, a death-trap for decentralised governance. They fear that this is intended to scuttle the role of local self-governing institutions in the sanctioning of projects, including take over of lands. Strangely, the new regulation [Section 14 (n) and 58 (n)] also prohibits anyone who has more than two children from contesting elections—obviously reinforcing the stereotype of Muslim demographics (Union Territory of Lakshadweep 2021d). The Population Foundation of India (PFI) says that the attempt to impose a two-child norm defies all logic as Lakshadweep has a low Total Fertility Rate (TFR) and an ageing population. PFI pointed out that as per the National Health and Family Survey – 5 (NFHS) 2019-2020, Lakshadweep has a TFR of 1.4 which is “far less than the national average of 2.2 and a cause for concern instead.” It also noted that the overall population growth rate for the Island has fallen to 6.3 per cent during the decade 2001-2011 from 17.19 pe cent in 1991-2001 (PFI 2021).

Adding insult to injury, the Lakshadweep Administration also brought in measures to divert the Island’s cargo to Mangalore which will result in undercutting the role of Kochi and Beypore. The captain of a passenger ship (who was earlier managing cargo ships also) told this writer that the move would ultimately deprive the traders of Kerala of all benefits of commercial transactions with the Island. Meanwhile, the Administration also lifted ban on liquor bars in the name of tourism. There were also widespread protests when the Island administration resorted to demolishing fish workers’ sheds on the beaches. This—accompanied by a series of other measures which included sacking of hundreds of temporary employees from services, transfer and demotion of native officials in the island administration, putting new regulations for air ambulance services etc—further intensified tension and anxieties among the islanders. There were already criticisms about diluting COVID-19 protocols in the Island, especially after the new Administrator took charge which, in fact, led to a surge in case load.

Many officials and former administrators of Lakshadweep found the ‘reform’ measures quite embarrassing. For example, Wajahat Habibullah, the administrator of Lakshadweep during 1987-90, wrote in an article that the measures being introduced in the Island are not in tune with the socio-ecological requirements of the Archipelago. He says that pursuit of ‘holistic development’, using the ‘claim’ that there has been no development in Lakshadweep for the past 70 years is wrong.” Habibullah also said that preventive detention law would undermine tribal land ownership with judicial remedy denied. Rejecting the ‘Maldives model,’ he said that any plans for Lakshadweep call for a “people-centric” approach in development which should “enrich the fragile coral ecology” (Habibullah 2021). Omesh Saigal, former chief secretary, Delhi and the administrator of Lakshadweep during 1982-85, also urged Union Home Minister to withdraw the controversial steps taken by Patel. In a letter, Saigal said that Patel’s drastic measures have created a lot of repercussions in the Island and turned the people against the Union Government. He said that Lakshadweep’s development and tourism promotion cannot be copied like Maldives and stopping meat from school meals would only create troubles (The Pioneer, 30 May 2021).

Why Ecology Matters for the Archipelago

About ten years ago, a planning commission Report of the Task Force on Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands in Environment & Forests For the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012 had warned that “Lakshadweep Islands are one of the low-lying small group of islands in the world and accordingly face the risks of inundation of sea water due to anticipated sea level rise, inundation of seawater due to storm surges as well as inundation of seawater due to Tsunami waves. These threats are associated with several uncertainties like the global warming leading to sea level rise, which is a slow and long-term process.” The Report further said that “Studies carried out by CESS under the project of Coastal Ocean Monitoring and Prediction System (COMAPS) indicate that the coral reef ecosystem is subjected to stress mainly due to anthropogenic pressures. Assessment of vulnerability of Lakshadweep Islands to both the natural and man-made hazards becomes multifold mainly due to their insularity, remoteness and geographical isolation from the mainland.” It also noted that “small size of these islands also acts as a barrier leading to high levels of vulnerability. As the islands lie scattered in the Arabian Sea, whenever a natural calamity occurs, the lifelines of these islands viz. communication and transportation are disrupted and the link between mainland and islands becomes non-functional…Other factors which contribute to vulnerability of these islands to natural and man-made hazards include social and economic backwardness of the indigenous population as well as fragile ecological, environmental and ecosystem status which directly affect their livelihood security due to hazards”(Planning Commission 2007).

The Report also underlined several risk factors in tourism promotion. While it was reckoned as an important source of income for the people, the Report noted that tourism “activities need to be carefully monitored and controlled as they cause a threat to the ecology of the island.” Likewise, “tourism related infrastructure development may also affect carrying capacity of these islands leading to pressure on natural resources.” It also warned that “destructive practices such as coral mining, dredging of navigational channels, unsustainable fishing practices, coastal development and souvenir collection are some of the major causes of environmental degradation on Lakshadweep islands.” From the Planning Commission Report, it is also palpable that “Lakshadweep islands are at risk from the natural hazards like storms, cyclones, sea level rise, rainfall and the associated factors like winds, waves, atmospheric pressure, storm surges, tsunamis, etc. In such events, the islands are likely to be inundated due to these forces and because of their low elevation levels” (Ibid).

Admittedly, island ecosystems across the world are seriously threatened today by a host of factors. The Indian Archipelago in the Arabian sea is no exception, especially when the Lakshadweep islands are small in size, and distance from the mainland shore is equally crucial. All these islands are bounded by ecologically sensitive coral reefs with the deep sea on the east and lagoon on the west. There are already several studies and reports on the fragile ecosystem of the Lakshadweep islands (Planning Commission 2008; Union Territory of Lakshadweep 2012: Anon 1989; Hoon 1997; James et al.1987; James 1989; James 2011).

If the Planning Commission of India had put across sufficient warning way back in 2007 and 2008—in respect of development activities in the Archipelago—its successor, NITI Aayog, does not seem to be concerned about such studies; nor is it worried about the future of the Island and its indigenous population. At least this is what is palpable from its ‘master plan’ for the ‘holistic development’ of the Islands.

But what is more worrying is the social matrix of communal mobilisation in the name of ‘development/underdevelopment’, and that too in a highly sensitive place like Lakshadweep which has not seen or heard any such hype or hysteria in the past. Ali Manikfan also shared his concerns of mounting communal polarisation in the mainland when issues at stake in the Island are more profound warranting serious rethinking.

The author wishes to thank Ali Manikfan, MN Karassery, N.P. Sreejesh, and several Islanders, traders and the crew of an Indian passenger ship for their comments and opinions.

References

Anon (1989): “Marine living resources of the Union Territory of Lakshadweep an indicative survey with suggestions for development,” CMFRI Bulletin, Vo1.43, 256.

Chari, Seshadri (2021): “Lakshadweep is key to India’s China strategy. Row over new rules hurts coastal security,” The Print, 28 May, https://theprint.in/opinion/lakshadweep-is-key-to-indias-china-strategy-row-over-new-rules-hurts-coastal-security/666831/

Didier, Brian J. (2004): “Conflict Self-Inflicted: Dispute, Incivility, and the Threat of Violence in an Indian Muslim Community,” The Journal of Asian Studies, 63(1), 61-80 (Retrieved June 1, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4133294)

Habibullah, Wajahat (2021): “A ‘reform wave’ Lakshadweep could do without,” The Hindu, 31 May, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/a-reform-wave-lakshadweep-could-do-without /article34684315.ece

Hoon, Vineeta (1997): “Coral reefs of India: review of their extent, condition, research and management status,” Proceedings of FAD Regional Workshop on the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Coral Reefs, Chennai: M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, and Bay of Bengal Programme (FAO).

India, Ministry of Home Affairs (2019): Crime in India 2019: Statistics Vol.1, National Crime Records Bureau, https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/CII%202019%20Volume%201.pdf

India, Ministry of Home Affairs (2020): “Meeting of the Island Development Agency focusing on ‘Green Development in the Islands to reach a new Height,” 13 January, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1599301

India, Press Information Bureau (2019): “PM’s address in the 5th Episode of ‘Mann Ki Baat 2.0’ on 27.10.2019,” https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1589328

India, Ministry of Home Affairs (2021): The Lakshadweep Panchayat Regulation, 2021, 25 February 2021,https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s358238e9ae2dd305d79c2ebc8c1883422/uploads/2021/02/2021022552.pdf

James, P.S.B.R., Pillai, P.P. and Jayaprakash, A.A. (1987): Impressions of a recent visit to Lakshadweep from the fisheries and marine biological perspectives. Marine Fisheries Information Service, Technical and Extension Series, CMFRI 72: 1-11.

James, P.S.B.R. (1989): “History of marine research in Lakshadweep,” CMFRI Bulletin, 43: 9-25.

James, P.S.B.R. (2011): “The Lakshadweep: Islands of Ecological Fragility, Environmental Sensitivity and Anthropogenic Vulnerability,” Journal of Coastal Environment, Vol. 2, No.1, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33018837.pdf

Logan, William (1887/2000): William Logan’s Malabar Manual, Vol.1 and Vol. 11, New Edition with Commentaries, State Editor P J Cherian, Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Kerala.

NITI Aayog (2019): Transforming the Islands Through Creativity & Innovation, May 2019, prepared by Jitendra Kumar and A. Muralidharan, New Delhi: The National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog, Government of India, https://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-07/Transforming-the-Islands-through-Creativity-%26-Innovation.pdf

PFI (2021): “Lakshadweep Administration’s proposed two-child norm defies all logic,” The Population Foundation of India, 28 May, https://populationfoundation.in/lakshadweep-administrations-proposed-two-child-norm-defies-all-logic/

Planning Commission (2008): Report on Visit to Lakshadweep – a coral reef wetland included under National Wetland Conservation and Management Programme of the Ministry of Environment & Forests. 30th October – 1st November 2008, New Delhi: Planning Commission Government of India, http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/Lakshadweep.pdf

Planning Commission (2007): Report of the Task Force on Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands in Environment & Forests for the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012, New Delhi: Planning Commission Government of India, https://niti.gov.in/planningcommission.gov.in/docs/aboutus /committee/wrkgrp11/tf11_Islands.pdf

Press Information Bureau (2021): “Sri Lankan Boat transporting 337 kgs Heroin intercepted,” 22 April, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1713450

Union Territory of Lakshadweep (2012): Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change (LAPCC) 2012, Union Territory of Lakshadweep Supported by UNDP, New Delhi: Department of Environment and Forestry, http://moef.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Lakshadweep.pdf

Union Territory of Lakshadweep (2020): The Lakshadweep Tourism Policy 2020, https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s358238e9ae2dd305d79c2ebc8c1883422/uploads/2020/05/2020052611.pdf

Union Territory of Lakshadweep (2021a): The Prevention of Anti-Social Activities Regulation (PASA), New Delhi: Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India, https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s358238e9ae2dd305d79c2ebc8c1883422/uploads/2021/01/2021012971.pdf

Union Territory of Lakshadweep (2021b): The Lakshadweep Animal Preservation Regulation, 2021, New Delhi: Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India, https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s358238e9ae2dd305d79c2ebc8c1883422/uploads/2021/02/2021022547.pdf

Union Territory of Lakshadweep(2021c): The Lakshadweep Panchayat Regulation, 2021, New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s358238e9ae2dd305d79c2ebc8c1883422/uploads/2021/02/2021022552.pdf

Union Territory of Lakshadweep (2021d): Lakshadweep Development Authority Regulation 2021, Promulgated by the President of India, New Delhi: Government of India, https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s358238e9ae2dd305d79c2ebc8c1883422/uploads/2021/04/2021042854.pdf

Venkatesan, T S (2021): “The curious support for Islamists’ Lakshadweep Propaganda by Kerala and Tamil Nadu Political Parties,” Organiser, 31 May, https://www.organiser.org//Encyc/2021/5/31/The-curious-support-for-Islamists-Lakshadweep-Propaganda-by-Kerala-and-Tamil-Nadu-Political-Parties.html

Excellent and insightful study which really cut across notions of nationalism, strategies of corporatised tourism and dangers implicating dehabitationwhich is the worst crime that you can do to an individual or a community. The political ecological and historic ecological making of the island is well concieved in this article. Ecology cannot be considered as another aspect of human civilization. It is Ecologies of the human and biological world that constitute the culture of a landscape. Lakshadweep in that sense is a cultural entity and any attempt to reconfigure it from the administrative view point is dangerous, both to the humans and to the nature.

Thanks Dr Sebastian for your comment

A very comprehensive and relevant write up.

An excellent objective, informative analysis; Thanks for sharing that

Thanks Azees