First published in Eurasia Review, 20 May 2021 with a repost in Global South Colloquy

Life for many expats in the Gulf/West Asian countries is part of a larger struggle against ever-increasing odds of daily encounters—be it war, terror attacks, recession or pandemic. Any news of a spark of fire or a whiff of fighting in the diaspora is distressing for more than 5 million emigrant-dependant families of the south Indian state of Kerala (euphemistically called ‘Gulf households’). This is important insofar as the emigrants from Kerala contribute the lion’s share of the expatriate base (as much as 2.5 million) in the Middle East region.

Stressed under conditions of work, stepped over by co-w Life for many expats in the Gulf/West Asian countries is part of a larger struggle against ever-increasing odds of daily encounters—be it war, terror attacks, recession or pandemic. Any news of a spark of fire or a whiff of fighting in the diaspora is distressing for more than 5 million emigrant-dependant families of the south Indian state of Kerala (euphemistically called ‘Gulf households’). This is important insofar as the emigrants from Kerala contribute the lion’s share of the expatriate base (as much as 2.5 million) in the Middle East region.

Stressed under conditions of work, stepped over by co-workers and employers, and in constant fear of expatriation in the wake of a war or loss of job—such is the daily grind for the Kerala expats who silently scratch out a living. The state witnessed several instances of repatriation following the Gulf war in the early 1990s and in subsequent episodes of fighting in several countries, such as Libya, Syria, Yemen, Iraq and so on. With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of India arranged special flights for people stranded in several countries in the region. The new episode of the Israeli-Palestine conflict has naturally generated added anxieties among the expats insofar as its impact can spill over to other GCC countries too.

‘Angels’ in Distress

It was in this perennial condition of strife and insecurity that the shocking news of the death of the 30-year-old Soumya Santhosh came from Israel. Soumya, who had been working for nearly 7 years as a care-giver at a Jewish household in Ashkelon, Israel, was killed in a rocket attack that struck their residence, fired by Islamic outfit Hamas who has been in control of Gaza since 2007. Soumya was one among hundreds of care-givers in Israel working to eke out their livelihood. Naturally, her unexpected death has set the alarm bell ringing for the family of expats living in the Middle East diaspora.

Ashkelon is close to the border and the area remains geostrategically sensitive given its proximity to Gaza. People in Ashkelon, as also in other southern Israeli cities like Ashdod, Dimona and Bersheva are accustomed to emergency drill and the area is heavily fortified, with tanks and armoured personnel due to the threat of attacks from Gaza. These are the places where more than 85,000 Jews of Indian origin have been living. Soumya and her 90-year-old charge, Naomi couldn’t escape to a safe destination as rockets began to hit residential places and the Israeli Iron Dome failed to intercept them. While Soumya lost her life on the spot, the ageing Naomi (reportedly a holocaust survivor) escaped with serious injuries, and she still remains in critical condition at Barzilai hospital in Ashkelon. The mayor of the city was reported to have admitted that nearly a quarter of the residents in Ashkelon did not have any access to safe zones during such rocket attacks. This is particularly important when the number of expats in these places is high.

Unlike the Indian emigrants in the GCC countries, the number and types of expats in Israel are different. Since the upgradation of India’s relations with Israel in 1992, there has been a significant change in the nature of migration and people-to-people contacts. According to the Indian Embassy in Tel Aviv, it was in the 1950s and 1960s that the early waves of Indian immigration into Israel took place. A significant number of them were from Maharashtra (Bene Israelis). There were also others from Kerala (Cochini Jews) and Kolkata (Baghdadi Jews), but their number was quite small. Of late, there were reports of immigration of Jews from Mizoram and Manipur (Bnei Menache) to Israel. The Ministry of External Affairs (India) says that there are about 97,467 Overseas Indians (OI) in Israel which include 12,467 Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) and 85,000 Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs). More than 98 per cent of the Indian citizens in Israel are working as care-givers and others are IT professionals, students and traders. Even as the new generation of these immigrant Jews got assimilated into the Israeli society, the older generation still retains their attachment to India. The changing nature of India-Israeli relations, in fact, facilitated the free movement of people from both sides. Unlike the migratory space in the GCC countries, the situation in Israel is different due to the nature and structure of emigrants. This is reflected in the response of the Israeli government in the aftermath of the rocket attack in Ashkelon.

Israel’s deputy chief of Mission to India, Rony Yedidia Clein, said that the family of Soumya would be “taken care of by the Israeli authorities in compensation for what happened, although nothing can ever compensate for the loss of a mother and wife.” The Charge De-Affairs at the Israel Embassy in Delhi also paid her last respects when her body was brought to India through the national capital. Later, Consulate General of Israel at Bengaluru, Jonathan Zadka, came to Kerala and paid his last respects at her home in Idukki district. In his brief note, Zadka said Soumya was “an angel who was killed in a cowardly attack.” He also promised Israeli government’s full support to Soumya’s family, especially her 9-year-old son.

In another development on 18 May, the Israeli President, Reuven Rivlin, spoke to the family of Soumya and expressed condolences on behalf of the Israel government and its people. Earlier, Israel’s Ambassador to India, Ron Malka, had also spoken to the family to express his sorrow over the incident. Meanwhile, the demise of Soumya also found its way into the UN Security Council records when Ambassador T S Tirumurti, India’s Permanent Representative to the UN, paid homage to her at the session.

Israel’s tribute to a Keralite killed in their homeland went beyond mere diplomatic gestures as they knew that Kerala— often carries the magical tag, ‘God’s Own Country’—has a much longer history in protecting all Semitic religions in the state. The Cochin Jews lived over two millennia on the Malabar Coast of Kerala and the first Jews, as some sources say, had arrived in the first century BCE as sailors on King Solomon’s boats and settled in the ancient port city of Muziris (presently Kodungallur). The Jews in Kerala were once a vibrant community of nearly 3,000 in the 1950s, but now only a few of elderly Jews remained in the Kochi city. Though most of the first-generation Jews had migrated to Israel after 1948, there are more than six synagogues well protected in the state—the Mattancherry Synagogue is among the most historically important one located in Fort Kochi.

Communal Frenzy

The news of Soumya’s death and the arrival of her mortal remains created waves of angst in Kerala which tended to polarise even the communal ties in the state. Whereas the support to the Palestine cause continued with several Muslim organisations appealing the believers to stand with the people of Palestine—as also the left parties in the state—the right-wing BJP-led Sangh Parivar outfits as well as some sections of Christian organisations whipped up anti-Muslim and Islamophobic campaigns. Some Christian youth organisations also unleashed social media hashtag campaign with slogans, such as “support to Israel” “Stand with Israel” “Down with Islamic terrorism” and so on. The campaign has been carried on by different denominations, but the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church (the major denomination among the Syrians) stirred up a communal whirl bringing to the fore issues from the past—from ‘love jihad’ to ‘halal food,’ Hagia Sophia issue and so on. Curiously, these were also the rallying points of the right-wing Sangh Parivar’s public frenzy for a long time. The BJP leaders went to the extent of portraying the left-front government as having legitimised the killing with “its support to the Islamist terror outfits like Hamas.” The left leaders, however, tried to explain its position saying that the entire showdown erupted with Israel’s provocative actions in Jerusalem which included the storming of the Al-Aqsa mosque. The State Committee of the CPI(M) also placed on record its deep condolences to the bereaved family. M.M. Mani, an outgoing minister of the left government cabinet, from Soumya’s home district in Kerala, also visited the family and assured all help.

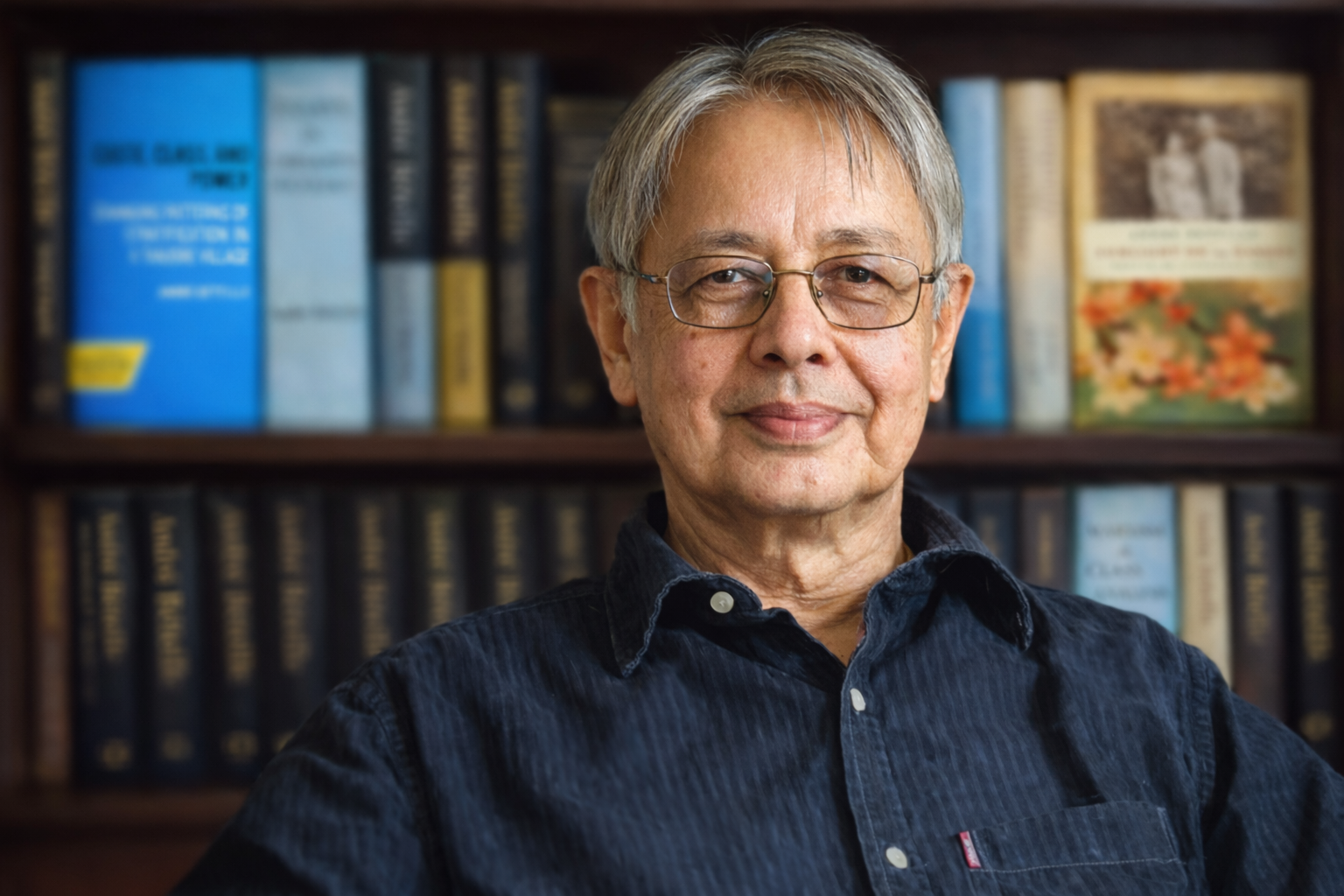

Soumya Sathosh

This is not the first time that the state of Kerala—which has been acclaimed for social harmony and secular history—witnessed such communal twists and turns. What makes the situation worse is the perverse use of social media by the various sections of religious (particularly youth) organisations with devious intentions of communal mobilisation. This, in fact, tends to undercut the social remittance of migration which the Kerala society has been effectively using for ‘bridging and bonding’ of social relations. As usual, during election time, this communal mobilisation finds a comfortable audience, particularly in the context of social disruptions caused by the pandemic. The fact that Kerala witnessed two consecutive elections in the recent past—one for the local bodies and the other for the state legislative assembly— underpins this scenario of communal mobilisation.

Declining Social Remittance?

One of the positive impacts of international migration is ‘social remittance’–a notion that underlines that migration leads to a new form of secularisation and cultural exchange that involve the transmission of ideas, practices, behaviour, skills, identities, and social capital between sending and receiving communities. This impact is to be ascertained in the life-world experience of migrants, their families and societies at large. A migrant is expected to be an agency of this who, after living in a country abroad and adapting to its ‘social facts’ of life, tries to reproduce a comparable pattern of life and mode of behaviour in his or her home country.

This, however, does not guarantee a universal pathway of ‘social remittance.’ For example, a migrant living in a country where fundamental human rights are denied would be transmitting a different sensibility of freedom given the social insights generated from conditions of subjugation. Many of the migrants in the GCC countries have this double burden of living with the conditions of particular migratory spaces, on the one hand, and engaging with general milieu of the receiving societies, on the other.

Kerala, for example, began to grapple with this complex expat life-world experiences—since the oil boom of 1970s—given its own burgeoning crisis in the employment sector. High unemployment, shrinking job opportunities and shifts in agricultural practices led to flow of unskilled and skilled labour to the GCC countries. While prospects of services job in the developed countries grew, a large number of trained doctors, engineers, teachers, nurses and other professionals began to move to countries in Europe, the U.S., Canada, Australia, Israel, Singapore and so on. Of the nearly 8.5 million non-resident Indians (NRIs) in the Middle East, almost 35 per cent are from Kerala and they are willing to discount freedom and civil rights, for the interim, in the host countries for a prospective remittance milieu of their homeland (for details see Seethi 2018; 2016).

However, the migration flow to the region has slowed down, over the years, and thereby there was a sudden surge in return migration with the onset of economic downturn, unpredictable oil prices, changes in labour regulations and, on the top of all, COVID-19 which has badly affected the millions of Indian expats working in the GCC countries, as well as the families and communities dependant on them. For the state of Kerala—which was already affected by two major floods in 2018 and 2019—these setbacks from the migratory spaces pose a major challenge. This naturally has a direct impact on Kerala’s economic and social remittances—with all attendant implications for social relations.

‘Angels’ in Demand

While the job prospects in the GCC countries remain shelved in the current impasse, particularly in the post-Arab Spring period, some continued to explore prospects of emigration in other destinations, such as Israel, Canada, Ireland, Italy, Australia and some countries in Southeast Asia. Nursing/Care-Giver is one profession which is still in demand in the developed countries due to the health issues of the ageing population, growing prevalence of chronic illnesses, shortages of physicians at the primary care level etc. However, migration was also prompted by the fact that nursing was not a well-paid profession in the state.

It may be noted, Kerala has a distinction of a high stock of nurses in the country. A World Health Organization study (2017), From Bain Drain to Brain Gain Migration of Nursing and Midwifery Workforce in the State of Kerala estimated that there were more than 68,000 nurses in the state and nearly 57 per cent of all emigrant nurses resided in the GCC countries (Saudi Arabia being the most favoured destination). The study also noted that the countries with a significant share of migrant nurses were the United States (6%), Canada (5.5%), and a smaller share in Australia, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Maldives and Singapore (2% to 3%). It said that nurse migrants to Australia also grew during this period. The study, however, pointed out that the emerging trends suggested that “while overall overseas nurse migration levels from Kerala are falling, there appears to be a shift in destination countries away from the Gulf countries to Canada and Australia.” In 2015, nurses were brought under the “emigration check required” (ECR) category and since then they were required to apply for clearance before emigrating to an ECR country.

Similarly, a European Union and European University Institute-commissioned study by Praveena Kodoth and Tina Kuriakose Jacob (2013), International Mobility of Nurses from Kerala (India)to the EU pointed out that the Syrian Christians, who were in search of alternative livelihoods, were in the forefront of taking up the nursing profession abroad. The study says that “migration of nurses from Kerala to Europe was embedded in the network of the Catholic Church. This provided a sense of legitimacy for migration.” “The church was an important part of the social context of the migrants.” It further pointed out that “these material conditions enabled the development of a migratory disposition among the Syrian Christians and enabled women to claim new kinds of spaces, breaking out of older norms of work and mobility. Because of the increase in the size of families, nursing jobs were expected to provide relief when it came to paying dowries. In this context, the legitimacy provided by the intervention of the Catholic Church could have been crucial in promoting aspirations among Christian women to study nursing and to take up overseas jobs.”

Though Israel did not provide a high demand market for nurses, the situation began to change in the last decade. According to a Report, Mainstreaming Ageing in Israel by the Permanent Mission of Israel to the United Nations and Other International Organizations in Geneva (2020), “the population in Israel is experiencing an accelerated process of ageing. Since 1950, the number of adults aged 65+ has increased 18-fold. Israel’s elderly population has some unique characteristics due to the fact that the country receives a steady stream of immigrants from 119 countries, including many who are Holocaust survivors, representing a wide range of ethnic, economic, health, educational and cultural differences.” Obviously, nurses from Kerala have found a new destination for livelihood. In Israel, according to recruiters in Kerala, a nurse can earn an annual salary of Rs.12-15 lakh although the working hours might be a bit longer. Many of those care-givers landed up in Israel due to accumulated debts and other financial liabilities. Soumya Santhosh may not be an exception here.

Why ‘Holy Land’ matters today

Evidently, the emotional outbursts and hashtag campaigns in the context of Soumya’s death cannot be seen in isolation. There has been a shift in the attitude of Christian community in Kerala on issues related to Israel and the ‘Holy Land.’ A migration studies scholar, Ginu Zacharia Oommen (2015), in his work on Gulf Migration, Social Remittances and Religion: The Changing dynamics of Kerala Christians (available with India’s Ministry of External Affairs website) says that “pilgrimage to Israel/Palestine (Holy Land) is extremely popular and thousands of believers from Kerala are undertaking a pilgrimage to Israel every year to visit holy sites. Though pilgrimage to Holy Land never existed in Kerala due to the costs, the practice is now quite popular among the Gulf migrants. The pilgrimage to Israel/Palestine is another significant aspect which is widely prevalent among Syrian Christian immigrants. Each year almost all the churches in GCC states organize a Pilgrimage via Jordan to the Holy Land especially during the summer vacations.” According to Ginu, it was perhaps “due to the influence of Gulf immigrants” that “the pilgrimage to Israel/Palestine has become very popular in Kerala too.” He says that the travel narratives of the “Gulf migrants to Israel and Palestine have had a tremendous impact amongst the people in Kerala and at present numerous travel and tour agencies have been facilitating the visits to Israel very frequently.”

Ginu has also brought to light another interesting turn in the episode. He says that “alongside the Holy land tours, the theory of ‘Biblical Israel’ is also penetrating into the society. The notion of ‘Biblical Israel’ is coined by American Episcopal Church in the 1970s and it also had indirect support of US Administration to justify enormous financial support to Israel.” Ginu pointed out that the conservative Christians in the U.S., particularly the Republican supporters “believed that the unequivocal support for Israel fulfills a Biblical injunction to protect the Jewish State.” “It is an insular and strategic philosophy to justify the occupation of Israel through the lens of Bible and the American Tele-Evangelists often stress on this aspect.” “Kerala with strong roots in eastern Orthodox history have been historically closer to the Arab/Chaldea/Syriac traditions than the notion of Israel.” He further argues that the theological understanding of Biblical Israel and tremendous support for Israelis has been “growing among the Christians in Kerala.”

Ginu also argues that the long stay and poorer working conditions of emigrants in the Muslim-dominated GCC countries created “a sense of alienation from the host country” and this difficult situation has been “used by the new generation churches to invigorate the idea of Biblical Israel.” He continues: “The support for Israel has largely entered into the Kerala coast through the active intervention of Gulf migrants and the neo-Pentecostal Church. Furthermore the Apostolic Zion Church in Kottayam conducts regular prayers for the wellbeing of Jewish nation and also promotes ‘Holy Land’ pilgrimage.” Ginu also cited a statement of an active member of ‘Grace Fellowship’ who said that his church was “quite active in teaching about the Israel,” as the knowledge of Israel was quite important “to understand the second coming of Israel.” He was quoted saying that they had “special prayers for Jewish land and the Church regularly organizes Holy Land ‘visits’ to Israel.” Ginu also quoted a statement of Fr K.M, George, former Principal of Syrian Orthodox Seminary, Kottayam who observed that “interest for Holy Land trips is very high among the Kerala Christians and this is indeed a new phenomenon. These trips had initially started among the migrant community in GCC countries in the late 1990s and finally Gulf migrants had introduced this to Kerala. Now the parishes across the denominations are competing each other to visit Israel. Some of the clergies are also running tour agencies to facilitate these visits.” Ginu’s observations have been testified by this writer in his interactions with some group leaders of the Christian community.

Obviously, the context of ‘stand with Israel’ campaign set in motion by Christian groups in the wake of Soumya’s death in Israel has much to do with the changing contours of the community mindset revolving around ‘Biblical Israel’ and the ‘Holy Land’ pilgrimage. However, this cannot be blown out of proportion to the level of Islamophobiac hyperbole as many Christian emigrants living in the GCC countries are well aware of the implications of whipping up any anti-Muslim campaigns—either in the host countries or in their home country. The leaders of some of these groups said that social media campaign has little importance beyond its contextual reaction. Interestingly, they are the ones who welcomed the ‘Abraham Accords’ signed by the UAE and Bahrain with Israel last year as they would keep open new avenues of pilgrimage to the Holy Land through the GCC countries. Though Soumya’s demise triggered an untoward social media campaign, it has not found its way into the mainstream discourses save the political statements of the BJP leaders.

The author wishes to thank Dr. Ginu Zacharia Oommen, Dr. Praveena Kodoth and Dr. Tina Kuriakose Jacob for their insightful studies and comments.

References

Kodoth, Praveena and Tina Kuriakose Jacob (2013): International Mobility of Nurses from Kerala (India)to the EU Prospects and Challenges with Special Reference to the Netherlands and Denmark, CARIM-India Research Report 2013/19, https://www.mea.gov.in/images/pdf/InternationalMobilityofNursesfromIndia.pdf

Oommen, Ginu Zacharia (2015): Gulf Migration, Social Remittances and Religion: The Changing dynamics of Kerala Christians, India Centre for Migration, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://mea.gov.in/images/attach/II_Ginu_Zachariah_Oommen.pdf

Permanent Mission of Israel to the United Nations and other International Organizations in Geneva (2020): Mainstreaming Ageing in Israel, https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/Israel_CN_EN.pdf

Seethi, K.M. (2018): “Distress Signals from Kerala’s Remittance Economy,” in Development Rebound: Challenges in Kerala’s Development Scenario Calicut: Raspberry; also see the article in Journal of Political Economy and Fiscal Federalism, Vol.2. 2016.

World Health Organisation study (2017), From Bain Drain to Brain Gain Migration of Nursing and Midwifery Workforce in the State of Kerala, https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/brain-drain-brain-gain/Migration-of-nursing-midwifery-in-KeralaWHO.pdf?ua=1