First Published in Eurasia Review, 4 May 2021

Amid new waves of COVID-19 in India, four states (West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Assam) and one Union Territory (Puducherry) went to polls in the past few weeks. The results that came on Sunday were devastating to the Indian National Congress (INC) in all polls in the states, and a grim warning to the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) in South India and West Bengal. Though Assam and Puducherry gave a sigh of relief for the BJP-led front, and West Bengal having provided more seats, its appeals to the electorates in Kerala and Tamil Nadu were squarely rejected by the people. These are the two states in south India that resisted the Modi wave, both in 2014 and 2019.

For Kerala, the results were not quite unexpected insofar as all pre-poll surveys and Exit polls had predicted re-election of the Left Democratic Front (LDF). However, it came as an overwhelming victory for the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M)-led LDF. The LDF literally swept the polls, winning 99 of the State Assembly’s 140 seats, an all-time record. It had secured 91 seats in the last elections. The INC-led United Democratic Front (UDF) faced one of its shattering defeats securing only 41 seats and INC’s own seats being shrunk to 21. Worse still, the BJP drew a blank with its political account in the lone seat (opened in the 2016 polls) in the state’s capital being closed.

The state of Kerala has been experimenting with ‘bipolar’ dispensations for quite a long time, alternating between UDF and LDF after every election. This is the first time that a political dispensation is getting a mandate for reelection and the anti-incumbency factor has been made quite irrelevant notwithstanding a heap of issues being put across by the opposition fronts.

The victory of the left front sends multiple messages. First and foremost, no major communal mobilization will work in the state given the complex combination of caste and religious demographics in the state. Nearly 45 per cent of the population (of the total 35 million) consists of religious minorities (Muslims and Christians). Nearly 40 per cent of the population consists of backward and depressed classes of the Hindu population. This naturally demands negotiations at different levels for a secular option under coalition dispensations. Religious and caste factors would have been deployed by political fronts at the time of elections (including in the selection of candidates in some constituencies with a particular demographic variant), but the state has witnessed people voting beyond religious lines.

A classic example is how people rejected the temple entry issue on Sabarimala. The wrangle over women’s entry into the Sabarimala temple (following the Supreme Court verdict in 2018 that granted permission to women of all ages to enter the temple) reached a high point in the local body elections held in December 2020 with the UDF and the BJP-led NDA blowing it out of proportions. But the left front clinched a remarkable victory in the local body elections. This has been repeated in the April 2021 elections with the two opposition fronts moving heaven and earth to browbeat the left front in the campaigns, even on the election day. But the results showed that the Sabarimala issue did not make any impact at all in electoral terms.

A similar issue was also deployed by political parties—based on the ‘cultural logic’ of Islamophobia. The Hindutva forces were in forefront in the campaigns, but secular parties too fell in line occasionally. Issues here varied from ‘Love Jihad’ to Triple Talaq and Hagia Sophia. It seems these issues did not matter at all in electoral terms.

Yet, two important decisions by the LDF government would have had a positive pay off—one in providing 10 per cent reservation to the economically weaker sections (EWS) and the other is other backward class (OBC) reservation to Nadar Christian communities. Moreover, the left front government has been so committed and determined in resisting the Hindutva agenda. For example, the LDF government took a decision that the State of Kerala would not implement the controversial Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), 2019 passed by Parliament given its inherent religious discriminatory provisions. It also piloted and passed a resolution in the State Assembly.

The second most important message is that the mandate of the people should be sought based on a set of clear-cut policies and programmes—rather than on ephemeral issues—which could be implemented within a timeframe. The left government has been so meticulous in drafting its election manifesto, after consultations with a range of stakeholders and experts in different areas. This seldom happens in electoral politics. A sort of bottom-up approach was found appropriate in this exercise of drafting a manifesto for change.

Social Securitization

The hallmark of the LDF manifesto (2021-26) was ‘social securitization’ with several programmes that sought to address questions of livelihood and social security. The manifesto put across a range of employment options which—through the role of both ‘provider and facilitator’—the state government aimed by generating 2 million opportunities for the educated through skill advancement and industrial restructuring. It also sought to bring in livelihood opportunities for half a million people in the farm sector and an additional one million in the non-farm sectors. Given its history of promoting start-ups, the manifesto assured that 15,000 new ventures will be initiated which would be generating an additional 1 lakh new jobs. Likewise, the manifesto promised to raise 3 lakh Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), from its present number of 1.4 lakh, which would also bring in more than half a million new employments.

A major aspect of the LDF social securitization scheme is its welfare pensions. When the LDF took charge in 2016, the amount was Rs.600 and that too was pending payment for more than a year and a half. The LDF raised the amount to Rs. 1600 and it promised to raise it to Rs. 2500 per month and for the first time women engaged in unpaid household work also would be brought under pension scheme. Honorarium for all scheme workers would be raised. Minimum wages also would be increased to Rs 700 daily or Rs 21,000 per month.

Among the other promises included are; an industrial investment totalling Rs.10,000 crore, creation of an electronic and pharmaceutical hub, 60 per cent increase in agriculture income, piped drinking water for households, universal broad-band internet coverage at an affordable rate, women empowerment, emphasis on water transport, environment protection, insulating the State against the ravages of climate change and hunger, and corruption-free State.

Housing for the poor has been one of the major priorities of the LDF government. During its tenure it had already completed 2.8 lakh houses and another 1.5 lakh more houses would be added soon through LIFE mission and other agencies. The manifesto also aims to build 5 lakh houses in the next five years mainly through apartment complexes for landless homeless, a total housing scheme for SC/ST families and one acre farmland to Schedule Tribes.

Kerala seems to be the only state which makes appropriation for SCP/TSP funds proportionate to their population in the state. The manifesto adheres to disburse funds for Tribal Sub-Plan through Oorukoottams (tribal neighbourhood groups) and offers MSP for minor forest products.

Health has also been a major area of state intervention, particularly in the background of the new wave of the pandemic. The state had already upgraded around 500 primary health centres to family health centres and made super specialty services available even at taluk and district hospitals. The LDF promises to extend the out-patient services in FHCs twice a day. The manifesto now proposes free in-patient treatment for up to Rs 5 lakh for 20 lakh families in both public and private hospitals and others would be covered under Karunya scheme for treatment up to Rs 2 lakhs.

The LDF manifesto also makes provisions for a lot of infrastructure projects which included power highways, gas pipelines, six-laning of national highways and a state wide fibre optic network aimed at digital revolution. The manifesto, while ensuring to protect the rights of the working class, also extends full co-operation to investors assuring that the LDF would take Kerala to the top ten Indian states in ‘Ease of Doing Business’ rankings. The LDF door to door campaigns reflected this commitment and promises while the UDF campaigns harped on transient issues.

Test of Political Adroitness

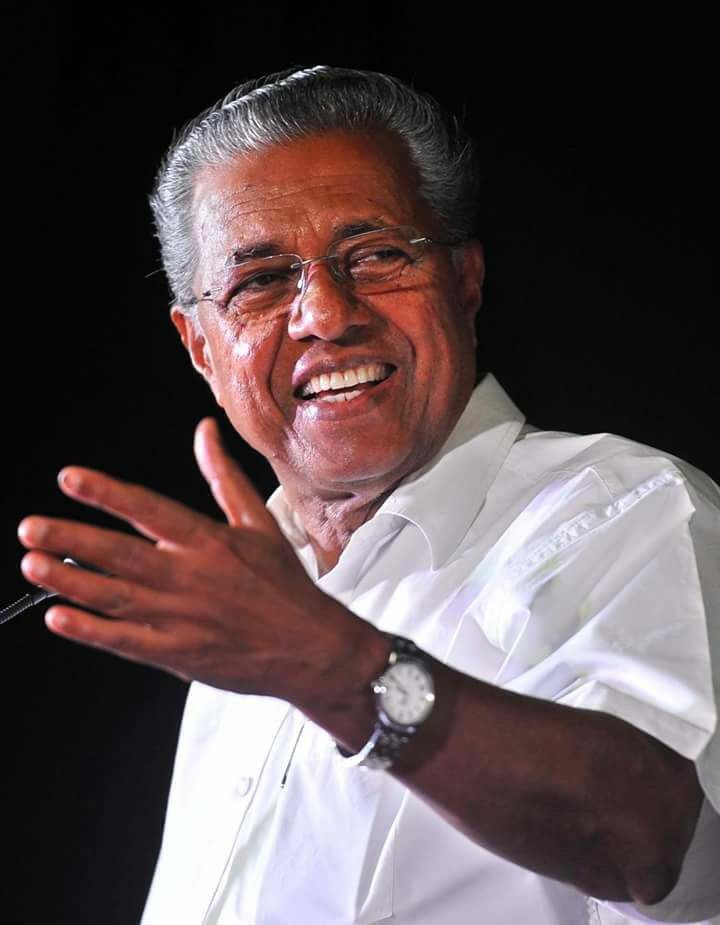

Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan has been the principal architect of an adaptive leadership of the LDF cabinet. The tenure of the LDF witnessed unprecedented crises—from the demonetization (2016) to Cyclone Ockhi (2017), two major floods (2018 and 2019), the outbreak of the Nipah virus disease (2019), to the most devastating pandemic, COVID-19 with its continuing repercussions for its migrant population living across the world. All caused tremendous pressure on the state’s economy and livelihood options, but the pandemic has literally strangulated the system necessitating health emergency measures and social securitization.

Here, the political adroitness of Pinarayi Vijayan could be seen in every moment of crisis. During the two major floods, this was so evident and even an average citizen in the state began to look upon the Chief Minister with considerable admiration and support. Social scientist Shiv Visvanathan noted that Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan was “a hands-on administrator” who “set a style emphasising concern with no self-denial, a clear-cut statement of the scale of the problem and the long-range effort required to address it.” He said: “Mr. Vijayan has no time for blame games or electoral politics. His even-tempered handling of the Centre and the southern States reflects a maturing of leadership. By avoiding nitpicking, he has brought a new maturity to the discourse on floods. There are no blame games but he is clear about the chain of responsibility.” Shiv Visvanathan wrote that Mr. Vijayan “signalled that his concern is with people first, regardless of ideology or religion. He has made sure that relief is not parochialised or seen through a party lens. He might be of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), or CPI(M), but he has convincingly acted as the Chief Minister of Kerala. All the malignant rumours spread by the right wing asking people to deny aid to Kerala as it helps missionaries leave him cold. He is clear about focus and priority, clear that this is not the time for electoral bickering or factional politics” (The Hindu, 28 August 2018).

Pinarayi Vijayan continued this adaptive leadership style in subsequent crises also. His evening press conferences, on all days of the crises, infused confidence in the people. In the process, he also sought to develop and sustain a different sort of ‘communicative rationality.’ This continued not just for a few days, but months after months since 2018 flood disaster. Moreover, during the pandemic, the Chief Minister also ensured that during the lockdown, and even months after that, every family in the state gets free food kits, distributed through the public distribution outlets. A lot of other medical emergency measures were also put in place.

Meanwhile, the opposition parties came up with a host of charges against the government with a view to taking political advantage in the upcoming elections. Allegations involving gold smuggling, dollar smuggling, ‘misappropriation’ of flood relief funds after the 2018 floods, the deep-sea fishing controversy and the charges of misuse of power for the Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIIFB) etc. were freely circulated. But the centrally controlled investigating agencies could not yet establish any serious charges against the political leadership. Most of the cases registered during this time remained incomplete or inconclusive. The LDF leadership also accused the Central government of misusing the investigating agencies for political mileage.

The 2021 electoral verdict is a vindication of the LDF claim that the people of the state who were kept close to their hearts would not desert them. The landslide victory is also seen as an acknowledgement of its model of governance and development.

A few days before the elections, T.M. Thomas Isaac, Finance Minister in the outgoing Kerala Cabinet said in an interview with The Hindu that it was “not just a re-election that the Left front is seeking in Kerala, but a mandate to build on the meticulously crafted model of governance and development in the years to come.” He said, “We want to make Kerala the Yenan of India.”

According to Isaac, “Kerala innovated and fashioned a model of fast-paced infrastructure growth to plug the deficit in that area, while simultaneously retaining its focus on welfare. Using the Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIIFB) vehicle, works that would have taken a quarter of a century to materialise in normal course were undertaken in a very short span of time. A beginning has been made and this has to be taken forward in such a way that it becomes a model for India.”

When Isaac talks about the ‘Yenan of India’ he evidently has a different development entity in mind—different from what Victor M. Fic had refereed to way back in 1970. The context of Fic’s volume Kerala: The Yenan of India: Rise of Communist Power 1937-1969 was clear. Kerala had emerged, in 1957, as the first Indian state to have a Communist government through ballot box. He situated the Kerala experience of communism in the broader context of developments since 1937, which he ended with a host of developments in the last years of 1960s. Fic concluded his work with the following statement:

If for the Communist forces Kerala represents Yenan where the basic strategic and tactical devices have been pioneered and applied, then for the forces committed to social change and progress under parliamentary democracy, Kerala should represent a laboratory of techniques which should have been developed and used and had not been, but which still can be resorted to and applied elsewhere to bring about the desirable alignments and winning combinations to give expression to the people’s will and checkmate the Communist calculus of power. Communism in India has been advancing during the past decades not because it represents in the eyes of millions of her poor an intrinsically superior and more efficient model of nation-building and modernization than can be provided by parliamentary democracy, but mainly because of the division of democratic camps and the ability of the former to maximise power through the united front and coalition politics.

Apparently, Fic’s analysis ended up with a position that the communist party’s ability to intervene in social issues was limited. The efforts put in place by successive left coalition dispensations, including land reforms and social security and welfare measures—of course within all limitations—seemed to have been underestimated. Even the debates on Kerala’s development experience (‘Kerala model of development’ for many) that emerged in the 1970s offered a different trajectory of the left intervention.

It is true that the advancement of the communist parties in India has been made difficult due to a number of factors. The rise of the right-wing communal forces and its patronage (through covert and overt means) by successive governments created an atmospheric setting for appropriation of institutions and policy regimes. In the post-emergency scenario, particularly after 1980s, this changeover—from a liberal setting to a combination of neoliberal statehood and cultural nation-building rhetoric—resulted in a complex situation of social insecurity and police raj. Consequently, the level of uneven development across states in India is so palpable. It is in this context that Thomas Isaac put across a new pathway of governance and development. Though Isaac (along with a few others) could not contest in the elections, due to the party’s new norms of ‘opening the door’ for the young political talents, the new Government which is set to assume office in a few days time, cannot gloss over the new development and governance agenda set by the outgoing team.

References

Anandan, S. (2021): “Aim is to Make Kerala the Yenan of India: Isaac,” The Hindu, 13 March.

Fic, Victor (1970): Kerala: Yenan of India (Rise of Communist Power 1937-1969), Bombay: Nachiketa Publications Private Limited.

Seethi, K.M. (2016): ” Left Front Victory in Kerala: A Verdict for Social Re-Engineering,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 51, No.22, 28 May.