First Published in Global South Colloquy, 5 September 2020

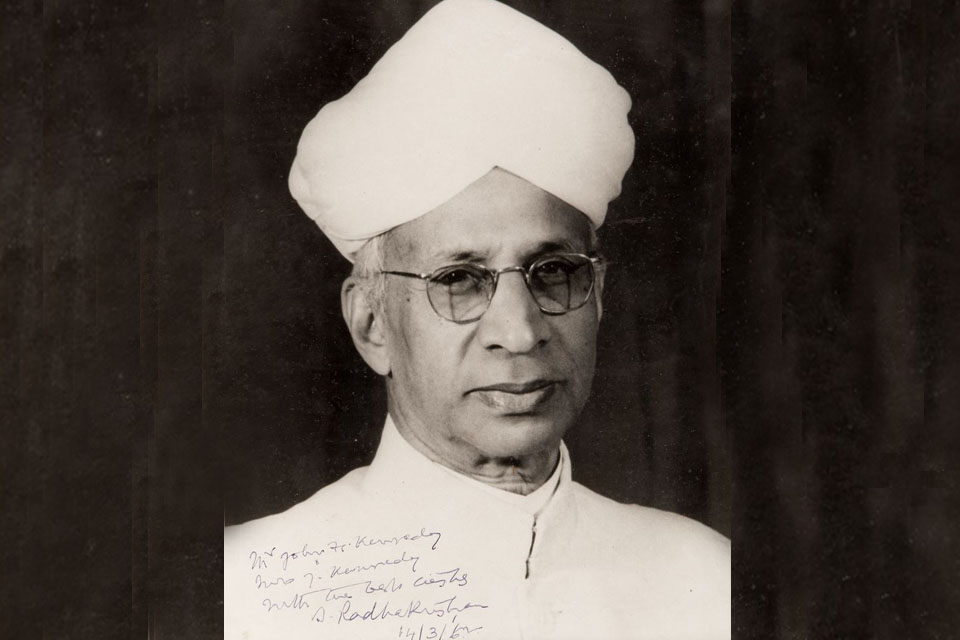

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, one of the captivating figures of modern India, has a number of facets to his complex personality. His long career as teacher of philosophy at Madras Presidency College, University of Mysore, University of Calcutta, University of Oxford, University of Chicago, as Vice Chancellor of Andhra University and Benares Hindu University, as Chairman of the First University Education Commission, as a diplomat, as Vice President of India (1952-62) and, later, as President of India (1962-67) were all outstanding, but they apparently overshadowed his role in the making of India’s foreign policy and worldview. Radhakrishnan’s stint as Representative of India to the League of Nations Committee for International Cooperation, his career in the UNESCO and distinct service as Ambassador to the Soviet Union in the crucial years of India’s independence (1949-52), role in the international organisations such as UN etc were equally remarkable. Radhakrishnan’s views and perspectives were as prominent as that of Jawaharlal Nehru and his colleagues in the South Block. It was Radhakrishnan who provided a spiritual-humanist dimension to India’s worldview while representing the country abroad. Many of his speeches and writings lend credence to this facet of India’s worldview.

Speaking at the Fourth Plenary Meeting of the Third Session of the General Conference of UNESCO held in Beirut in November 1948, Radhakrishnan, as the leader of the Indian delegation, said:

The threat which hangs over human civilization is the symptom of a desperate moral need. There can be no stable future for the world without a spiritual revolution- without a transformation of human motivation. A good world cannot be built on pride or selfishness, hatred or injustice, greed or lust for power. Thucydides said long ago that this power lust is “like a wicked courtesan which makes nation after nation in love with her and betrays them one after another to their ruin.” Napoleon, Kaiser and Hitler; and who knows if human folly has run its full course. A spiritual renewal is necessary if the world is to be saved. A new purpose must co-ordinate our Education, our Science and our Culture, make them integral elements of a world view which should inspire all our activities. The Koran says: “Verily, God will not change the conditions of men till they change what is in themselves” (UNESCO 2009: 10-11).

Radhakrishnan, who was a member of the Executive Board of UNESCO in 1948 and, later, President of the UNESCO General Conference in 1952 warned that we were “running the risk of allowing ourselves to be obsessed by the inevitability of the catastrophe.” Rather than “trying to prevent a war, we are more concerned about winning it if it came. This growing fatalism is an ominous sign of our times. There is a psychological retreat from peace and approach to war” (Ibid). This speech came a few months after the Truman Doctrine and Marshall Plan which ushered in the battel lines of the Cold War across the strategic hotspots of the world. The period was marked by intense strategic experiments embedded in a two-world (bipolar) ideological matrix. This was a crucial moment in India’s foreign policy formation with stalwarts like V.K. Krishna Menon, K.M. Panikkar, K.P. S. Menon et al. playing a major role in Nehru’s decision making—echoing the spirt of ‘freedom of action’ in international affairs.

S. Radhakrishanan addressing UNESCO Conference

Delivering McGill’s first Beatty Memorial Lecture in 1954—Canada’s one of the longest running lecture series— Radhakrishnan (as India’s first Vice President) said:

Whether we like it or not we live in one world and require to be educated to a common conception of human purpose and destiny. The different nations should live together as members of the human race; not as hostile entities but as friendly partners in the endeavour of civilisation. The strong shall help the weak and all shall belong to the one world federation of free nations…The separation of East and West is over. The history of the new world, the one world, has begun (Radhakrishnan 1955: 130-31).

Radhakrishnan talked about ‘one world’ and ‘world federation’ in a critical juncture of the post-war world situation marked by ideological mêlées and strategic brawls between the two contenting blocs led by the United States and Soviet Union. The idea of non-alignment was also getting global currency and a collectivity flair among the newly independent countries of Asia and Africa.

Crucial Days in Moscow

In Moscow, Radhakrishnan had a comfortable time notwithstanding Stalin’s early reservations about India. We may recall, Stalin even refused to meet free India’s first Ambassador to Moscow—Vijaya Lakshmi—Prime Minister’s sister, despite repeated requests. Stalin treated her differently and that resulted in confining her to the Indian Embassy, strangely. During Stalin’s period, the Indian Mission did not have even a proper building. It was set up in a suite in Hotel Metropole. It was during the “long and illustrious tenure” of K.P.S. Menon that the Mission was shifted to an independent building (known as Dom Druzbi), according to I.K. Gujral who later occupied the office in Moscow (Gujral 2011:58).

President Radhakrishnan in Moscow in 1964

Radhakrishnan was the first Indian diplomat who met Stalin, and that came three years after independence. The second and the last meeting came in 1952 after two years, and the meeting reflected the changing mood in Kremlin – just three days before Radhakrishnan left Moscow. There were interesting moments in the meeting with Stalin which gave, perhaps, the first hints of Moscow’s change of policy towards New Delhi. During the course of his conversation with Stalin, Ambassador Radhakrishnan said that “India was as much against capitalist exploitation as Russia and it had the same economic objective.” “But we wish to adopt peaceful parliamentary methods to achieve our aims, because our whole history has taught us that enduring progress should be of a peaceful character ” (Indian Embassy, Moscow 1953).

To this Stalin said: “But the exploiters will never quit – they will very seriously object to quit.”

Ambassador Radhakrishnan said that, in any case, we would “try our own methods very hard, and if we succeeded it would be a great lesson to other nations.”

Towards the end of the conversation, Ambassador Radhakrishnan asked if Stalin would like to put to him any questions.

Stalin said that he had only one question, and that was about ‘our Correspondent’ in India. He turned to Vyshinsky (Soviet Foreign Minister from 1949 to 1953) and asked what ‘this complaint’ was. Vyshinsky explained that we had felt that Borzenko’s articles were unfair and unnecessarily critical of the Government of India, etc., and added that Prime Minister Nehru had also complained to Novikov about this (perhaps, this is not correct. We have been informed that the Foreign Secretary had seen the Soviet Ambassador). “That is all right, recall him,” Stalin said to Vyshinsky. “We will recall him”, Stalin said to Ambassador Radhakrishnan, “If you don’t like him, you tell us frankly. We assure you that he will be recalled.”

Ambassador Radhakrishnan said that his own anxiety was that the good relations and friendship that we had built up here in Moscow should not be spoilt by Soviet representatives in India saying things which offend our national dignity.

“Are there such people?” Stalin asked.

“Yes,” the Ambassador said, “that is what we feel about Borzenko and the Moscow Radio.”

Stalin again turned to Vyshinsky and quietly said, “Call him back.”

Ambassador Radhakrishnan then referred to his “imminent return and his anxiety for preserving Indo-Soviet friendship.” Stalin said that he was “glad of the latter.” “Both you and Mr. Nehru are persons whom we do not consider to be our enemies. This “will continue to be our policy and you can count on our help”. Then he went on, “Our people have been educated in the equal treatment of Asian people” – and he said this with some feeling. “The United States and Britain look on Asian peoples as backward and look down upon them. We treat all Asians as equals. It is this which helps us to conduct a correct policy. The Americans and the British treat them superciliously [sic]. Our policy helps us to have very different relations with the Asian peoples.” Stalin spoke “slowly, deliberately and with obvious feelings,” according to the Indian Mission documents (Ibid).

Referring to our foreign policy, Dr. Radhakrishnan said that it was not unlike that of the Soviet Union in several matters – China, Japan, Korea or, for that matter, the admission of other nations to the UN. “We are not with America and we are not with any power,” he stressed, “We act according to our sense of right and do not yield to any political or economic pressure ” (Ibid).

Beyond South Block

It was during Radhakrishnan’s career as Vice President (1952-62) that India, for the first time, engaged the Afro-Asian community at Bandung in 1955 that eventually led to the formation of the largest Global South collectivity – the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) at Belgrade in 1961. It was also during this period that New Delhi and Moscow came closer on a variety of issues, including on the Kashmir question, and the support to the strengthening of India’s public sector which commenced with the Bhilai steel plant. Besides the major steel plants in Bhilai and Bokaro, India also augmented its energy infrastructure and most of the heavy and basic industries, vital for its development, with the assistance of Moscow. Thermal power stations, the Heavy Machine Building Plant in Ranchi, the Coal Mining Machinery Plant in Durgapur, the BHEL Heavy Electrical Equipment Plant at Haridwar, the Korba Coal Mining Project, the Bharat Ophthalmic Glass Ltd in Durgapur, the Bharat Pumps and Compressors Ltd in Naini, the IDPL Antibiotics Plant in Rishikesh, the Synthetic Drug Project in Hyderabad and the Surgical Instruments Plant in Madras, space research and development collaboration etc. were other major achievements.

In September 1957, Radhakrishnan was on a three-week foreign visit as India’s Vice President. The visit also included a visit to China where Radhakrishnan met Mao Zedong. When Radhakrishnan reached Mao Zedong’s residence in China, Mao himself came out to receive the then Vice President of India. Radhakrishnan’s tenure as President (1962-67), however, witnessed the most critical issues of Indian diplomacy and security– the India-China war (1962), the Sino-Pak border pact (1963), China’s nuclear test (1964) and India-Pakistan war on Rann of Kutch and Kashmir (1965). His period also witnessed another case of the third-party mediation in India-Pakistan conflict which heralded with the Tashkent Agreement (1966) with the Soviet mediation (the earlier ones were the World Bank mediation for the Indus-water dispute and the British mediation of the Rann of Kutch conflict). It was also during his tenure as President that India unofficially approved the subterranean nuclear explosion project in 1966. But Radhakrishnan’s views on nuclear weapons were already well known. While addressing the UN General Assembly, just three years back (1963), he said:

The piling up of armaments and nuclear tests… do not give us much hope. We feel that if these armaments go on piling up and if these stockpiles increase, by accident, or by mistaken, the world may burst into fragments. Even if that does not happen, when there are nuclear tests they are bound to injure, not only present generations, but also generations still unborn. We deliberately consign thousands and thousands of young children throughout the world to this kind of decadence, physical and mental (UN 1963).

Radhakrishnan also reminded:

We are the victims of the nationalist and militarist kind of society. Other nations were regarded as supreme, and for achieving the aims and political ambitions of those nations we hitherto resorted to the use of force. But we have come to a condition when the nation -State has to be subordinated to the larger concept of world community. Unless we are able to do it, unless we give up the use of force, which is intolerable, detestable and wicked in the world where nuclear weapons have developed, it will not be possible for us to bring about peace in the world (Ibid).

He also forewarned that nationalism “is not the highest concept. The highest concept is world community.” Radhakrishnan said that it was unfortunate that we were still the victims of concepts which remained ‘outmoded’ and which were ‘outdated’ (Ibid). He, however, saw the solution from the world’s troubles in the right type of religion. He said Hinduism, shorn of its aberrations, is an example. The spiritual humanism which Radhakrishnan espoused has a strong pluralist undercurrent. He says:

We recognise different religions, but discern the unity underlying them. We do not want to flatten out diversity or impose uniformity. Difference should not mean discord. Each religion while maintaining its individuality will learn to appreciate the validity of the others. We do not believe in any favoured races or chosen people or exclusive truths. Our seers extended hospitality to all faiths (Radhakrishnan 1963).

Radhakrishnan was more or less recapitulating Swami Vivekananda’s formulations on the theme. For example, on 11 September 1893, Swami Vivekananda, during his much-reverberated speech in Chicago, said:

I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true. I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and the refugees of all religions and all nations of the earth. I am proud to tell you that we have gathered in our bosom the purest remnant of the Israelites, who came to the southern India and took refuge with us in the very year in which their holy temple was shattered to pieces by Roman tyranny. I am proud to belong to the religion which has sheltered and is still fostering the remnant of the grand Zoroastrian nation (Vivekananda 1970).

Again, during his concluding speech on 27 September, Vivekananda said:

Much has been said of the common ground of religious unity. I am not going just now to venture my own theory. But if anyone here hopes that this unity will come by the triumph of any one of the religions and the destruction of the others, to him I say, “Brother, yours is an impossible hope.” …The Christian is not to become a Hindu or a Buddhist, nor a Hindu or a Buddhist to become a Christian. But each must assimilate the spirit of the others and yet preserve his individuality and grow according to his own law of growth (Ibid).

The philosophical and spiritual questions Radhakrishnan raised across international fora are still relevant even after decades. The most crucial challenge has been how to negotiate between national sovereignty and global commitments. The concepts of ‘one world’ and ‘world federation’ espoused by Radhakrishnan might be problematic for many, in an era of unilateralism and selective justice, but for a large number of countries in the Global South, it is an aspiration that perfectly fits in with their long-cherished dream of democratising international relations.

References

Indian Embassy, Moscow (1953): “Record of the Conversation of J.V. Stalin and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, 5 April 1952,” https://www.revolutionarydemocracy.org/rdv12n1/3convers.htm

Gujral, I.K. (2011): Matters of Discretion: An Autobiography, New Delhi: Hay House.

Radhakrishnan, S. (1955): East and West. Some Reflections, Beatty Memorial Lectures, London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Radhakrishnan, S. (1963): Occasional Speeches and Writings, July 1959- May 1962, Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India

Radhakrishnan, S. (1965): President Radhakrishnan’s Speeches and Writings, May 1962-May 1964, Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India

UN (1963): Statement By Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, President of India at the United Nations General Assembly, 10 June 1963, https://pminewyork.org/pdf/uploadpdf/12644lms16.pdf

UNESCO (2009): Paths To Peace: India’s Voices in UNESCO: 64 years of UNESCO-India Co-operation, New Delhi: UNESCO.

Vivekananda, Swami (1970): The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Mayavati Edition, Volume 1, Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama.