Can the subaltern speak for himself?

K.M.Seethi

First Published in The Hindu, January 27, 2016

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/Can-the-subaltern-speak-for-himself/article14021582.ece

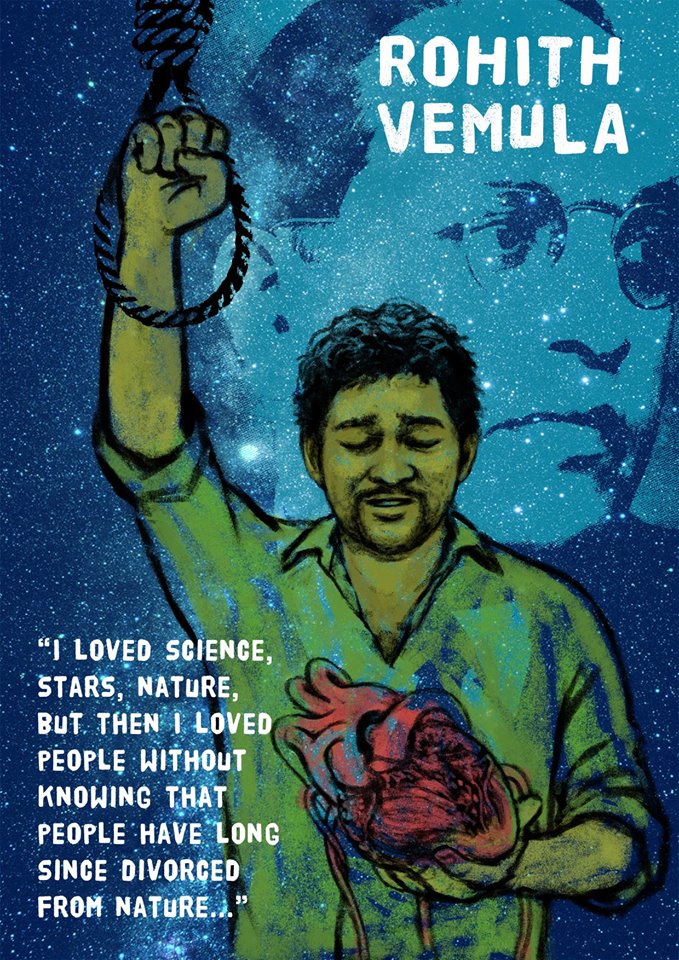

The outrage in the wake of Rohith Vemula’s ‘social murder’ in the campus of the University of Hyderabad raises more questions about the identity and integrity of the institutions of higher learning in India.

Sadly, every attempt has also been made to divert the issue from the public domain by intermixing facts with fiction. Earlier, it was placed within a larger “national/anti-national” discourse. Then it was narrowed down to the issue of a “law and order” problem on the campus. To add to the list of such woes, Rohith’s identity has also been dragged to a stage when his mother had to emerge to defend and clarify facts.

‘Rohith’ is a reminder that ‘subalterns’ cannot speak the truth, either for themselves or for others. Neither can ‘others’ speak for subalterns. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who drafted the Indian Constitution, argued that “unlike a drop of water which loses its identity when it joins the ocean, man does not lose his being in the society in which he lives… Man is born not for the development of the society alone, but for the development of his self.” Are we blatantly denying this ‘self’ to many Rohiths? Why did Dr. Ambedkar talk about this ‘self’? Because he knew that this nation need not necessarily represent the ‘self’ of the subalterns collectively. ‘Great’ nationalists cannot comprehend the chemistry of this relationship between the “body and soul” about which Rohith had written in his letter. The power/knowledge discourse appears to hold no good any longer when subalterns cannot even have the right to die. Really, a fate worse than ‘death’!

The changing campus

Most campuses have, of late, become melting pots of anxieties/tensions and feelings of deprivation, marginalisation and alienation. Nobody asks why this happens so often now. Has it got something to do with a ‘new division of labour’ in institutions of higher learning? From the point of view of shrinking social spaces, both academic and sociological, on campuses, consequent upon a ‘new class culture’ being superimposed on the stakeholders of higher education. Obviously, the subalterns are the worst victims of this ‘new class culture’ due to the long-term consequences of social stratification prevailing. More than that, the supposed beneficiaries of the ‘new education’ are the most volatile ones, due to the multiplied uncertainties of the future, the accumulated debts emerging from educational expenses, the rolling back of educational subsidies, cutting down of the number of fellowships/scholarships (limiting itself to a new class of beneficiaries), the lack of burden-sharing social spaces, the decline (and degeneration) of mainstream political forces on campuses, and an increasing acceptance of a highly individualised social Darwinian mindset.

Added to this list are emerging anxieties with regard to the role and responsibilities as well as the institutional-management culture of the present-day educational realm. The commodified notion of education creates nothing but an ‘individualised social Darwinian mindset’. This is not peculiar to campuses alone, which represent only a spectrum of our social space. Whatever happens in this larger social space, from family to the communities, from social organisations to the state, will have its inevitable impact on these thinking and acting beings on campuses. Our children are surely more volatile, more uncertain, more inhibited than they were about two decades back. They may be more skilled, more knowledgeable, more sophisticated and more active today. Yet, their skills, knowledge, sophistication and activity hide the absence of a larger social world in their mind and hearts.

Frustration with institutional and social decay induces new psychological choices, perhaps tragic ones too. This will lead to what Émile Durkheim calls some sort of self-demoralisation: “Man cannot become attached to higher aims and submit to a rule if he sees nothing above him to which he belongs. To free him from all social pressure is to abandon him to himself and demoralise him.” This may or may not create social atmospheric pressure for societies to stabilise themselves, if not for transforming them, but Rohith will remain a symbol of this ‘transformative stage’ because of his ‘politics of representation’. The extra-statutory death penalty which he decided for himself is actually for the entire set of social engineers of our time. Rohith already knew that there were so many skeletons in the social cupboard that not many on and off the campus would be willing to unload them for a real-time change.

Omissions of inquiry

Now that the Union government has announced a judicial inquiry, everyone is expecting the agitating students to go back to the classroom. The victims are, in fact, the first to know that these are political exercises in social futility. The history of judicial commissions shows that they are generally confessions of the failure of the existing political apparatus in dealing with extraordinary situations. Many such reports continue to gather dust on government shelves. However, they tend to serve one major purpose, that is, to provide the state with a convenient escape route to release the accumulated tensions in the system. Victims are to believe that justice will eventfully prevail. This notion of ‘prevalence’ is a continuing saga in the statute culture of the civilised world. Subalterns will never accept the premise that this farcical exercise will help emancipate them. Rather, they will continue to believe that every inquiry is an attempt to legitimise a fait accompli loaded against the victims. In Rohith’s case, facts are too well known. The culprits are among us. But who will bell the big cats?