K.M.SEETHI

First Published in Countercurrents, 9 September 2018.

https://countercurrents.org/2018/09/09/bolstering-nepal-china-connectivity-kathmandu-goes-beyond-a-zero-sum-game-in-south-asia/

Nepal and China have made a significant step in bilateral relations by finalizing the text of the protocol to the proposed agreement that would help facilitate Nepal to use Chinese sea and land ports for third country trade. This has come as a sequel to the signing of the Transit and Transportation Agreement by Prime Minister K P Oli two years ago, in March 2016, in the wake of the Indian blockade through the southern border. The present move is surely a major challenge to India’s decades-old Nepal policy. Kathmandu’s dependence on New Delhi is apparently coming to an end with Nepal having greater access to the Chinese sea and land ports for trade. The announcement of the Kathmandu-Beijing deal came when New Delhi was also worried about a news that Nepal Army decided to pull out from the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) level military exercise following the Prime Minister’s direction on Friday. KP Oli is reported to have asked the national defence force not to participate in the drill, compelling the Army’s leadership to rollback its earlier decision to take part in the first ever military exercise at the regional grouping level initiated by India. The decision was flashed just a day before the military contingent squad was expected to reach Pune, where the drill would commence on Monday.

Meanwhile the projected Nepal-China transit agreement is seen as a significant victory in the Himalayan state’s long-cherished deal to end the Indian monopoly. A major pay-off of the deal is that Kathmandu can use four Chinese seaports, three land ports for third country import, and export through the six dedicated transit points between Nepal and China. China is reported to have agreed to allow Nepal use Tianjin, Shenzhen, Lianyungang and Zhanjiang seaports and Lanzhou, Lhasa and Xigatse dry ports for trading with third countries. An official of the Ministry of Commerce and Supplies told reporters that the “Chinese side is also open for Nepal to use its other seaports if Nepal requires them.” The text-finalized would be inked when a high-level team from China would visit Nepal. It may even be during the visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping which is yet to be scheduled (Kathmandu Post 2018).

It is also expected that Nepali shipments from Japan, South Korea and other north Asian countries could be sent through China which would reduce shipping time and costs. Overland trade is currently through Kolkata which is apparently taking considerable time. India also opened Vishakhapatnam port for Nepali trade. More than the issue of proper roads and customs infrastructure on the Nepalese side of the border, experts say the connectivity distance is also a factor—the nearest Chinese port is also located more than 2,600 from its border. A key challenge to implementing the agreement will certainly be the existing connectivity. Nepal’s roads to China need urgent improvement and augmentation. The existing infrastructure on Nepal’s side of the border, including highways and dry ports, is too inadequate and they all must undergo immediate repairs and replacements to facilitate imports and exports. Though the two countries had agreed in 2012 to open six dedicated land routes (Humla, Korola, Rasuawagadhi, Tatopani, Olangchung Gola and Kimangthanka), only the Rasuwagahadi-Kerung route is operational as of now (Ibid).

New Delhi’s concerns could be understandable. Currently, 98 per cent of Nepal’s third country trade goes through the port of Kolkata. India has also two rail lines under construction and three more are under consideration to boost trade ties. India and Nepal had 25 crossing points, two integrated checkpoints and 2 more checkpoints were under construction.

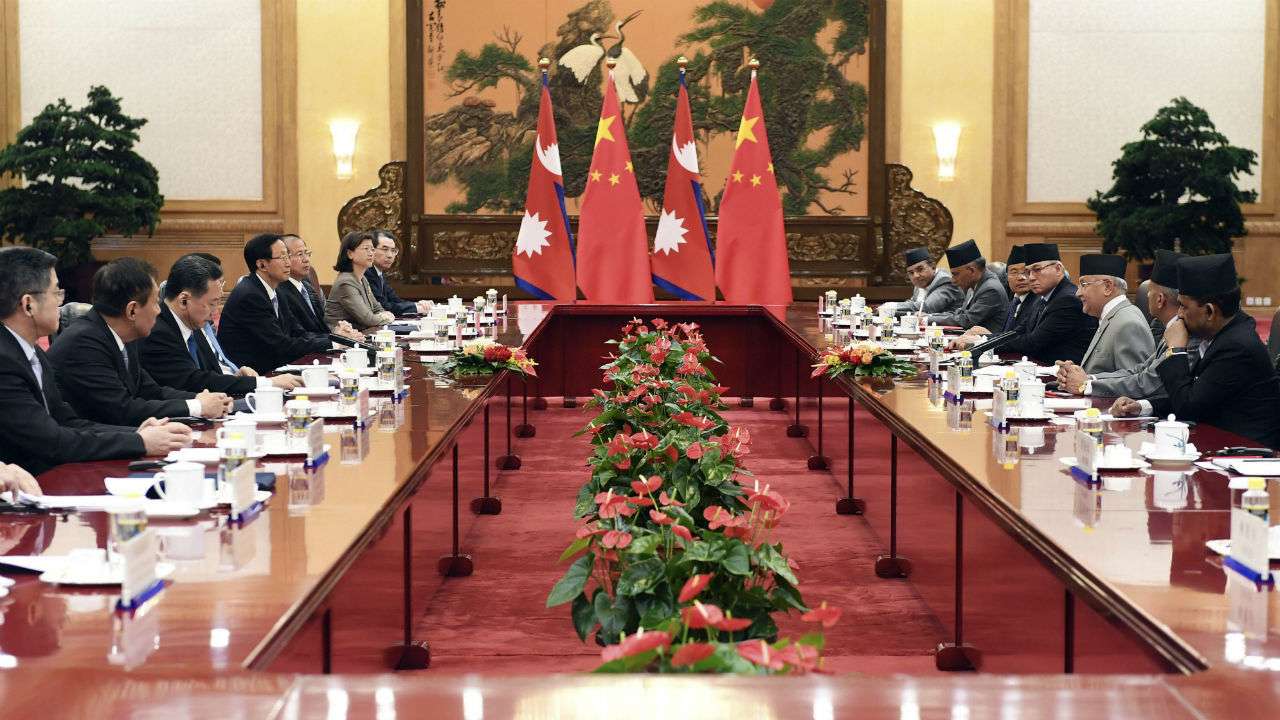

However, it was in the background of the difficulties that Nepal had gone through during 2015-16 that the country had initiated the process of diversifying its trade options. During the visit of Prime Minister K P Oli to China in June 2018, some major steps were taken. The Joint Statement issued, then, between China and Nepal clearly indicated their decision “to intensify implementation of the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative to enhance connectivity, encompassing such vital components as ports, roads, railways, aviation and communications within the overarching framework of trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network” (China, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2018). The two countries also “agreed to reopen the Zhangmu/Khasa port at an early date; improve the operation of the Jilong/Keyrung port; ensure the sound operation of Araniko Highway; and carry out the repair, maintenance and improvement of Syaphrubesi-Rasuwagadhi Highway and push forward the construction of a bridge over Karnali river at Hilsa of Pulan/Yari port at an early date. To ensure the inter-connectivity and smooth running of the infrastructures above, the Nepali side will complete the disaster treatment around the Tatopani Port and along the Araniko Highway, maintain Kathmandu-Syaphrubesi Highway in operational condition.” Besides the signing of the MOU on Cooperation for Railway Connectivity, the Nepali side “expressed its willingness to speed up the development of the three North-South Economic Corridors in Nepal, namely Koshi Economic Corridor, Gandaki Economic Corridor and Karnali Economic Corridor in order to create jobs and improve local livelihood, and stimulate economic growth and development in those areas. Both sides agreed to further study on the possibility of cooperation on the above corridors.” The Joint Statement further noted: “Underlying the importance of generating a win-win situation for both countries, the two sides will constructively engage in finalizing the joint feasibility study on China-Nepal Free Trade Agreement (FTA). The two sides will strengthen cooperation both at central and local levels to promote establishing cross-border economic cooperation zones as per the MOU signed between the two countries” (Ibid).

Major sections of the Nepali population still believe that India was primarily responsible for the months-long blockade in September 2015- February 2016, just as it was for more than a year in 1989, which brought in unprecedented hardships for the people. The Post Disaster Assessment: Blockade 2015/16, a report brought out by the Nepal Economic Forum (NEF) documented the cost of the blockade on the Nepali economy (Nepal Economic Forum 2016). As the trade blockade continued for months, vital supplies to Nepal were virtually cut-off. The energy crisis that set in with the blockade had its impact felt across all the sectors of the economy. Even essential imports like medicines were not allowed to enter the country. Whereas the instant impacts of were widely reported, the long-term effects of the blockade appeared to be more complex and enduring.

The Report says that the agriculture “took a nosedive during the blockade, affecting the incomes and livelihoods of almost 70% of the population.” There was a “crippling shortage of petroleum products such as petrol, diesel, kerosene and cooking gas.” There was also “shortage of medicines, hospital and surgical equipment and vaccines. Severe shortage of fossil fuel coupled with power-cuts affected all sectors of the economy, spawning a grave economic crisis.” “Most industries shutdown with those in operations doing so below capacity.” There was industrial raw material in short supply as most industries in Nepal depended upon raw material imported from/through India. Construction sector suffered as shortage of fuel and construction material dents high hopes of boom in the sector owing to post-quake reconstruction. Nepal also reeled “under hours of load-shedding coupled with fossil fuel shortage… As industries and factories shut down or operated below capacity, a large number of industrial workers were rendered unemployed” (Ibid).

The Report said that as many as “3.47 million children in the central and eastern plains alone were affected due to the closure of educational institutions following the unrest that gripped the region for months…” “Given almost two-thirds of medicines consumed in Nepal are imported from India and that raw materials for those produced within the country also come Primarily through India, border blockade led to country-wide shortage of medicines, including life-saving drugs, adversely affecting health service operations (Ibid).

The first stalemate occurred during 1969 after the expiration of the 1950 Trade and Transit Treaty, New Delhi imposed quantitative restrictions on cross border transactions. Imports and exports fell by 10.7% and 23.2% during 1969 and 1970 respectively GDP growth rate decreased from 4.4% to 2.5%, despite increased government expenditure and improvements in the agriculture growth rate. (Ibid: 5). The1989 blockade came following the expiry of the trade and transit treaties, which by this point had been separated into two different treaties i.e. Treaty of Trade and Treaty of Transit.

What triggered the blockade in 1989 were a few issues like the introduction of work permits system for Indians by Nepal as a rejoinder to expulsion of Nepali speaking people by India in its states, Nepal’s acquisition of arms from China and its refusal to incorporate New Delhi’s wishes for a single comprehensive trade and transit treaty. This brought in 15 months of economic hardship for Nepal with an embargo on 19 out of 21 bilateral trade routes and 13 out of 15 transit routes. Growth in imports and exports fell by 30% and 24% following the blockade compared to 40% and 51% in FY 1987-88. Growth in exports dropped from 37% to 2% during the blockade while imports still rose at 17% during 1987-88 to 1988-89. The Report says that “compared to 1969, the economy was considerably affected though not to the extent of the 2015-16 blockade.”According to the NRB report “Impact of unofficial Indian blockade on Nepal’s economy,” the impact of 1989 blockade had relatively less far reaching implications than the current blockade given that the economy in 1989 was relatively self-reliant on food with agriculture contributing about 60% to the GDP, transport usage limited to just 3.8% (approximately 74,000) of the current number of vehicles, 95% of total cooking methods involving traditional wood-fire cooking, and energy demands met through hydropower. It is notable here that prior to the 1989 blockade, the share of Indian imports to total imports was relatively low at 33%; whereas currently, the figure is twice as much (Ibid: 5-6).

The Report while concluding made the following recommendation:

Nepal’s excessive dependence upon India for international trade and transit was a major reason for the economic hardship that ensued once the southern border points were obstructed. The country has to look to diversify international trade and engage with multiple trading partners. With regards to transit, the singing of a transit agreement with China is a welcome move on Nepal’s part. This should now be followed up with proactive engagement with the Chinese government to enhance infrastructure in the northern entry points in order to facilitate seamless transit of goods at rates much cheaper than at present (Ibid: 65-66).

Nepal’s latest engagement is obviously a follow-up of a chain of events, commitments and recommendations. It may be recalled that during his visit to China in June 2018, Nepali Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli had briefed in an interview that Nepal would “serve as a bridge between our two neighbours (India and China). In fact, we want to move from the state of a land-locked to a land-linked country through the development of adequate cross border connectivity. Our friendship with both neighbours places us in an advantageous position to realize this goal” (GT 2018). Clearly, Nepal has been contemplating a move from “the state of a land-locked to a land-linked country through the development of adequate cross border connectivity” (Seethi 2018).

Admittedly, Nepal has quite legitimate aspirations under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLS). Article125 of the Convention on the Law of the Sea states:

Right of access to and from the sea and freedom of transit:

1. Land-locked States shall have the right of access to and from the sea for the purpose of exercising the rights provided for in this Convention including those relating to the freedom of the high seas and the common heritage of mankind. To this end, land-locked States shall enjoy freedom of transit through the territory of transit States by all means of transport.

2. The terms and modalities for exercising freedom of transit shall be agreed between the land-locked States and transit States concerned through bilateral, subregional or regional agreements.

3. Transit States, in the exercise of their full sovereignty over their territory, shall have the right to take all measures necessary to ensure that the rights and facilities provided for in this Part for land-locked States shall in no way infringe their legitimate interests (UN 1982:68).

Nepal’s position is further supported by the Vienna Programme of Action for Landlocked Developing Countries for the Decade 2014-2024, adopted by the Second United Nations Conference on Landlocked Developing Countries in 2014(Fenzel 2015). It sought to promote the economic growth of developing, landlocked countries through the expansion of transit systems. The Vienna Programme thus called for “unfettered access” to the sea for landlocked countries, and an expansion of international transportation infrastructure (Fenzel 2015). Moreover, Nepal has also a legitimate claim to make under Article V of the GATT. Article V calls for “freedom of transit” of goods through the member country territories, using “routes most convenient for international transit.” Even as reasonable customs regulations are admissible, the unilateral blockading of another member state runs contrary to the goals of Article V (WTO 1994; Fenzel 2015).

India, Nepal and China are signatories of the UNCLS, WTO and a host of other international conventions and treaties. Nepal being a land-locked country can press for its legitimate aspirations as per the relevant provisions of these regimes, besides its status as a least developing country. As such India cannot legally put additional pressure on Nepal to ‘look only South.’ Kathmandu at the same time knows that New Delhi cannot be unfairly sidelined for historical and cultural reasons given the significant size of the Nepali nationals in India and the Indian diaspora in Nepal. This is also at a time when India and China have been major trade partners, besides both sharing a common platform under the BRICS, SCO etc. Thus, New Delhi cannot unilaterally impose any additional burden on the tiny Himalayan State for its long-cherished aspirations for trade diversification and greater connectivity with the outside world.

References

China, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2018): “Joint Statement between the People’s Republic of China and Nepal, 22 June, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zzjg_663340/yzs_663350/gjlb_663354/2752_663508/2753_663510/t1570977.shtml

Fenzel, Daniel (2015): “The Indian Blockade of Nepal, Access to the Sea, and Freedom of Transit: An Opportunity to Vindicate the Rights of Landlocked Countries,” Journal of International Law, 19 November, available at http://blogs.law.gonzaga.edu/gjil/2015/11/the-indian-blockade-of-nepal-access-to-the-sea-and-freedom-of-transit-an-opportunity-to-vindicate-the-rights-of-landlocked-countries/

GT (2018): “Nepal can be a bridge between China and India” Global Times, 21 June, at http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1107848.shtml

Kathmandu Post (2018): “China allows Nepal access to its ports,” 8 September, http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/printedition/news/2018-09-08/china-allows-nepal-access-to-its-ports.html

Nepal Economic Forum (2016): Post Disaster Assessment: Blockade 2015-16, https://nepaleconomicforum.org/portfolio/post-disaster-assessment-blockade-2015-16/

Seethi, K.M. (2018): “The Quest for ‘Zone of Peace’ in the Himalayas – Nepal’s Critical Engagements with India and China,” Countercurrents, 5 July, https://countercurrents.org/2018/07/05/the-quest-for-zone-of-peace-in-the-himalayas-nepals-critical-engagements-with-india-and-china/

UN (1982): United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

WTO (1994): Article V, Freedom of Transit, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/ai17_e/gatt1994_art5_gatt47.pdf